International Organizations in the Linguistic Context of Quebec

International Business Master's thesis

Julia Sulonen 2011

International Organizations in the Linguistic Context of Quebec

Master’s Thesis Julia Sulonen Spring 2011

International Business

Approved in the Department of Management and International Business __ / __20___ and awarded the grade ____

1. Examiner 2. Examiner

Aalto University School of Economics

Master’s Thesis Abstract

Julia Sulonen May 17th, 2011

International Organizations in the Linguistic Context of Quebec

PURPOSE OF THE STUDY

This study sets out to investigate the linguistic context of the province of Quebec (Canada) from three angles. Firstly, it examines what components context can be seen to compose of. Secondly, the channels through which these components can influence international companies are explored. The third research goal is to analyze the resulting effects on international organizations’

operations in this context.

DATA

The main data source used is qualitative interviews, which were held with companies (3), a university business faculty, and an institutional body. Secondary data from websites and company and governmental publications along with some personal observations are used to complement the interview data.

FRAMEWORK

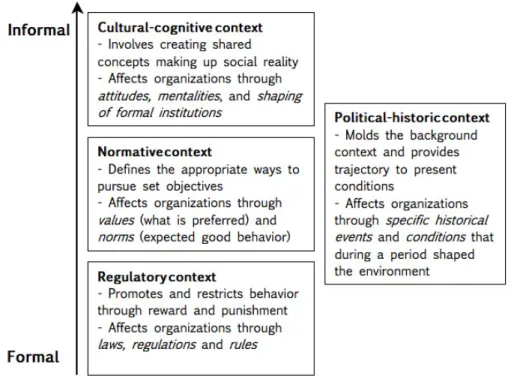

The political-historic context and institutions are distinguished as key components of the Quebecer context. Institutions are further divided as follows: the cultural-cognitive context (influencing organizations through attitudes and mentalities), the normative context (influencing through norms and values), and the regulatory context (influencing through laws and regulations).

FINDINGS AND CONCLUSIONS

Findings suggest that the political-historic backdrop, involving the longstanding oppression of Francophone rights, has shaped the unique linguistic context of Quebec markedly. In institutions, the cultural-cognitive and normative contexts comprise of i.a. the protective attitudes towards French against the threat of English. The regulatory context is shown to set linguistic limitations to international organizations in the province: the law prohibits the use any other official language than French and demands its dominant position in operations. Having a language strategy in Quebec is therefore challenging. Regardless of the increasing need for proficiency in English, the strict regulations lag behind, restricting international operations and consuming resources. This is perceived by organizations as an entry barrier and a potential reason to move business elsewhere.

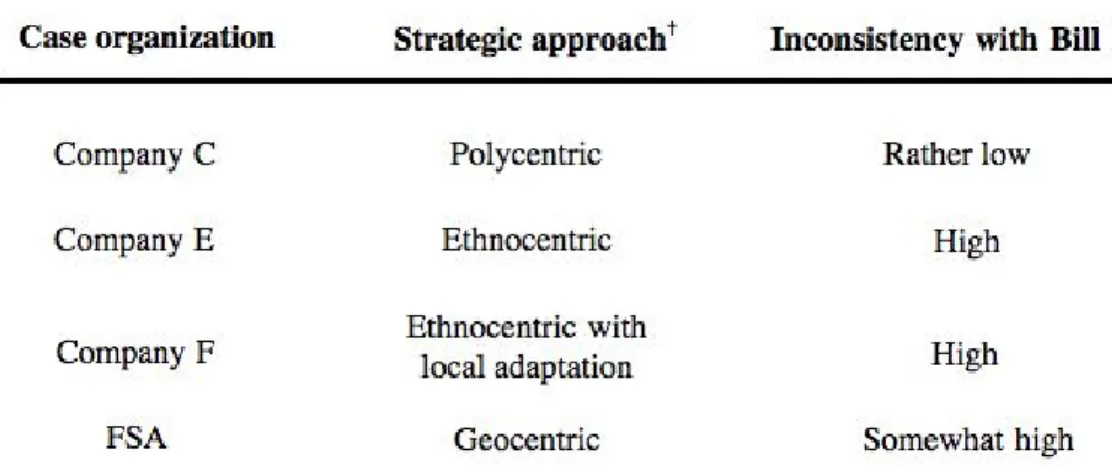

The mission of the governmental body implementing the language law has not been adjusted to the internationalizing marketplace and is therefore deemed somewhat obsolete. International organizations are faced with linguistic duality; the contradicting demands of the local law and the requirement to conduct global business operations in English. The strength of this duality depends on the organization’s strategic orientation: for those employing local adaptation conformation comes rather naturally, whereas a globally integrated approach is in conflict with the law. The key contributions of this study are the novel, multi-perspective approach combining historical/contemporary, national/provincial, and organizational/institutional angles, and the evaluation of bilingualism in an organizational context, which has remained scarce to date.

KEYWORDS Language, language strategy, language laws, bilingualism, corporate language, role of language, context, institutions, regulations

A

CKNOWLEDGEMENTSI would like to give thanks first of all to Patrick Hurley and Zhan Su at FSA of Université Laval, who made the research internship for the duration of the thesis project possible.

Mr. Su should additionally be thanked for his contribution to the case study of FSA.

Thanks go also to the representants of the other case organizations, who cannot for confidentiality reasons be named here. Their contribution was however essential for the success of the study.

In the search for case organizations, irreplaceable advice was gotten from certain acquaintances in Quebec City. These tips made the process of finding suitable companies considerably faster than was expected.

Finally, a special thank you to Rebecca Piekkari. She not only suggested her thesis group for me based on my interests, but agreed to supervise the thesis in the unusual long- distance circumstances.

T

ABLE OFC

ONTENTS1. I

NTRODUCTION... 3

1.1 BACKGROUND OF THE STUDY ... 4

1.2 OBJECTIVES OF THE STUDY AND RESEARCH QUESTIONS ... 7

1.3 DEFINITIONS ... 8

1.4 LIMITATIONS ... 9

1.5 STRUCTURE OF THE STUDY ...10

2. L

ITERATURER

EVIEW... 12

2.1 CONTEXT ...12

2.1.1 What is context? ...12

2.1.2 Contextualization ...13

2.1.3 Components of context and their channels of influence ...15

2.2 LANGUAGE IN INTERNATIONAL BUSINESS ...20

2.2.1 English as a lingua franca of business ...21

2.2.2 Language policies and strategies of MNCs ...23

2.2.3 National language planning ...25

2.2.4 Language skills, training and promotion ...26

2.2.5 Languages used in MNCs ...28

3. M

ETHODOLOGY... 33

3.1 CASE STUDY AS A RESEARCH STRATEGY ...33

3.1.1 Alternative case study approaches ...34

3.1.2 Contextualized explanation ...35

3.2 CHOICE AND PRESENTATION OF THE CASE ORGANIZATIONS ...38

4.1.1 FSA of Université Laval ...38

4.1.2 Office Québécois de la Langue Française ...39

4.1.3 Company C ...41

4.1.4 Company E ...41

4.1.5 Company F ...42

3.3 THE QUALITATIVE INTERVIEW ...43

3.4 DATA COLLECTION AND VERIFICATION ...46

3.5 VALIDITY AND RELIABILITY ...48

3.6 LIMITATIONS OF THE RESEARCHER ...50

4. F

INDINGS... 53

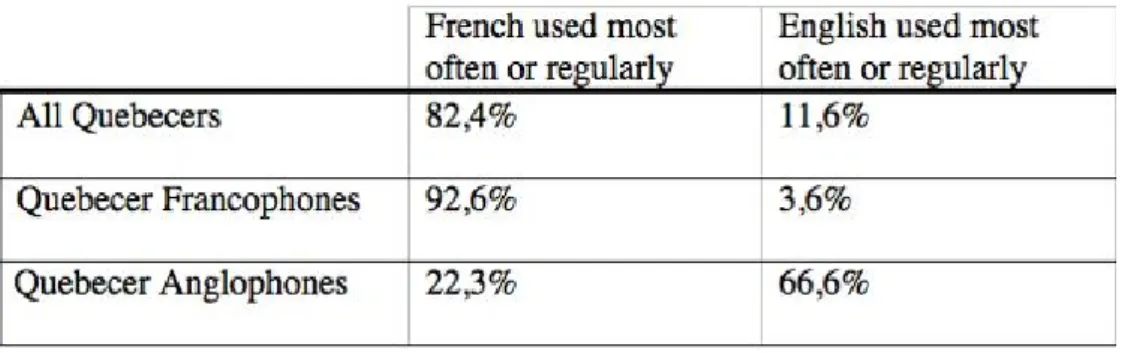

4.2 BILINGUALISM IN QUEBEC ...53

4.2.1 History of bilingualism ...54

4.2.2 Linguistic legislation in Canada ...56

4.2.3 Language regulation in Quebec ...58

4.2.4 Bilingualism in figures ...61

4.2.5 The reality of bilingualism in Quebec’s business ...64

4.3 INSTITUTIONAL PRESSURES REGARDING LANGUAGES ...68

4.3.1 Language strategy limitations in the context of Quebec ...68

4.3.2 Bill 101 and the ‘Language Police’ ...74

4.4 LANGUAGES OF BUSINESS IN THE CASE ORGANIZATIONS ...79

4.4.1 Increasing importance of English ...79

4.4.2 Linguistic duality ...81

4.5 HR ACTIVITIES:RECRUITMENT, TRAINING AND PROMOTION ...83

4.5.1 Language as a selection criterion ...83

4.5.2 Language training ...86

4.5.3 Language skills as promotion requirements ...88

4.6 LANGUAGE REGULATIONS AND COMPETITIVENESS ...89

5. C

ONCLUSION... 93

5.1 MAIN FINDINGS ...93

5.2 MANAGERIAL IMPLICATIONS ...100

5.3 LIMITATIONS AND SUGGESTIONS FOR FUTURE RESEARCH ...101

R

EFERENCES... 103

A

PPENDIXA – I

NTERVIEW DETAILS... 112

A

PPENDIXB – I

NTERVIEW GUIDE... 113

T

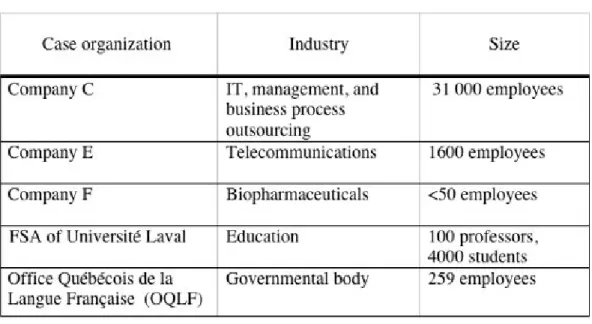

ABLES TABLE 1.DATA SOURCES USED ...37TABLE 2.CASE ORGANIZATIONS, INDUSTRIES, AND SIZES ...43

TABLE 3.WORKING LANGUAGES IN QUEBEC IN 2001 ...62

TABLE 4.CONTRADICTION BETWEEN CASE ORGANIZATION STRATEGIES AND BILL 101 ...74

F

IGURES FIGURE 1.ELEMENTS OF CONTEXT AND THEIR EFFECTS ON ORGANIZATIONS ...17FIGURE 2.COMPONENTS OF CONTEXT AND THEIR CHANNELS OF INFLUENCE CONTRASTED ...32

FIGURE 3.APPROACHES TO CASE STUDIES ...35

FIGURE 4.KEY FINDINGS PLACED IN THE THEORETICAL FRAMEWORK ...93

1. Introduction

"Linguistic duality is everybody's business. It can only succeed in Canada if the majority accepts the reasons for it and fully supports it. Bilingualism in the 1970s was aimed at institutional change, but now it can be considered a personal and collective asset in an era of globalization. To give young people a chance to be bilingual is to give them a tremendous opportunity for cultural enrichment and help them participate in the new knowledge and information economy."

Dyane Adam, Commissioner of Official Languages

As multiculturalism is a fundamental characteristic of international business today, one would expect a large volume of studies to be focused on its elements and their implications to doing business. Among these is inevitably language, which forms a major part of any culture. However, language and its impact in international business emerged as a standalone research topic only in the late 1990’s. Before this the role of language was studied, but as a part of a broader set of factors encompassed by culture. The emergence of MNCs in global business has undoubtedly contributed to the increased attention language issues receive today.

A country whose national identity is very much determined by its linguistic duality is Canada. Due to its bilingualism and the resulting necessity to manage the different linguistic groups, Canada has a reputation of encouraging diversity and thus continues to attract immigrants from around the world. It is publicly recognized - i.a. by The official body governing bilingualism in Canada, the Office of the Commissioner of Official Languages (OCOL), and the Institute for Research and Public Policy - that this gives the country an advantage in global competition: Canada’s bilingual brand allows better access to markets that share either one or both of its two languages.

Bilingualism in Canada and especially Quebec has a long and controversial history, and the two language groups are a significant dimension of the country’s past and present.

The French-English relations have passed through several phases, many of which have

been characterized by misunderstanding, injustice, and prejudice, especially from the Francophone point of view. In the Canada of today, most of these controversies have been overcome, but realizing the ideal of a linguistically equal opportunity country still requires work.

The role of bilingualism in Quebec’s business world is particularly interesting due to its paradoxical nature. From the longstanding historical power struggle of the French population under British rule, to the multicultural, officially bilingual and tolerant country Canada is considered to be today, the linguistic context and its implications for business are likely to be unique in the world.

1.1 Background of the study

Marschan-Piekkari et al. (2004, 247) recognize the scarcity of discussion on context in organization studies over the 1980’s and 1990’s. Only in the 21st century did qualitative research method handbooks start to put more emphasis on the research process and the factors affecting it. This discussion has largely been centered on the organizational context, with the internal workings of the MNC as a key research object. Topics studied include i.a. the implications of the multinational organization context to team learning and performance (Zellmer-Bruhn & Gibson, 2006) and the impacts of career capital of international assignments within distinct organizational contexts (Dickmann & Doherty, 2008). The external context of the international firm has been quite a popular topic of studies as well, with research focusing on e.g. the implications of operating in different national environments (e.g. Punnett & Shenkar, 1994), international best practice transfers and context embeddedness (Dinur et al., 2009), and especially the cultural and linguistic barriers affecting cross-border HQ-subsidiary relationships (Harzing & Feely, 2008; Harzing et al., in press; Barner-Rasmussen & Aarnio, in press). These two perspectives have also been combined, for instance by Tregaskis et al. (2010), who looked at transnational learning in multinational firms and how this is affected by both organizational context and national embeddedness.

However, more detailed levels of context still remain widely unexplored, for instance, different contexts prevailing within a country. In general, the existing research on the topic sees context either as a background element having certain effects on the research process, or a broader definition of the operating environment (i.a. a country’s national context). Specific, unique contexts that impose particular demands on certain types of companies remain virtually unstudied to date. The bilingual environment of Quebec is an example of such a context. As Cai (2007) states, context drives the way phenomena are perceived and abstracted by researchers at a conceptual level, and this process results in new categorizations and relationships. Therefore context can be used to derive new knowledge.

A significant part of context for international companies today is formed by the different national cultures of the countries of operation, along with their languages. The ‘language issue’ received scant attention for a long period of time, as pointed out by several studies (Reeves & Wright 1996, Verrept 2000 in Harzing et al. in press, Welch at al. 2001 and 2005, Harzing & Feely 2008). Even though special issues of International Studies in Management & Organization (2005) and, more recently, Journal of World Business (2010) have shed considerably more light on the language issue and its implications for HQ-subsidiary relationships, many areas of language in international business remain ignored.

As Welch et al. (2001) argue, traditional international business literature has tended to bundle language together with culture, and the associated problems together with

‘cultural distance’. These authors sought to separate language from being dealt with as a component of culture, and to investigate whether the adoption of English as a corporate language facilitates internal communications or actually creates added cross-cultural issues. In the aforementioned special issue of Journal of World Business, Harzing et al.

(in press) also recognize that cultural differences as barriers in international business are today widely accepted, but language diversity has continued to receive very limited attention.

It comes as no surprise, then, that bilingualism and its role in international company operations is even less researched. Bilingualism has been and is researched mainly from the phonetic and linguistic perspectives, and especially in the educational setting (many studies focus on the effects of a bilingual education and its learning trade-offs, see e.g.

Dylan, 2010). Spanish speaking workers in the U.S have been studied some (e.g. Winston

& Walstad, 2006 looked at recruitment and diversity in the context of bilingualism and library services), but hardly any studies exist on the bilingual environment and what kinds of demands it creates for international organizations operating in this context.

Existing work that comes closest to this topic has looked at e.g. how employees of multilingual organizations in Switzerland conceptualize the use of different languages (Steyaert et al., in press), how four official languages operate in a global non- governmental company (Lehtovaara, 2009), the role of Finnish and other languages at the multilingual workplace (Piekkari, 2010), and language management and policies in corporate communications in general (e.g. Andersen & Rasmussen 2004, Dhir & Gòkè- Parionlà 2002). The bilingual environment of Quebec, as well as its development and history have been extensively studied in sociolinguistics (e.g. Cobarrubias 1983, Wardhaugh 2006, Kaplan & Baldauf 1997). Studying bilingualism from a business perspective is much rarer. The only Canadian study on bilingualism in an organizational context is a review of bilingualism in the Canadian armed forces in 1763-1969 (Pariseau

& Bernier, 1986). In the field of economy, Canadian bilingualism was a popular topic especially during the 1970’s when the economics of English vs. French1 were a heated political topic. For an overview on these studies see Vaillancourt (1985). The research on bilingualism from an organizational perspective has thus been scattered even in a geographical area where its historical importance has been paramount. Also globally the role of language in international business has varied markedly from one discipline to another, as is discussed next.

1The economics of a language entail the comparison and evaluation of its benefits as opposed to another language, in order to determine which one to use. The key socioeconomic indicator in this evaluation is usually the effect of language on income (Vaillancourt, 1985)

Chapman et al. (2004, 297) state that a considerable difference in attitude can be seen between IB research and social anthropology when it comes to dual and multiple language use. The latter regards linguistic competence as a necessary element of cultural expertise. Contrarily, in IB the prevalent language used has become English along with its adoption as the lingua franca of global business. These authors claim that this has more profound implications for research, as in social anthropology language is considered part of the specific socially constructed context in question. Language mismatches are thus a key point of interest. IB researchers, however, are said to often have a more positivist outlook on the world, seeing language as a quantifiable issue that can be documented (leading to e.g. translation issues being experienced as lack of expertise in English, not opportunities to discover cultural differences). (Ibid, 297)

1.2 Objectives of the study and research questions

Combining these two deficiencies in past research - the lack of studies on context as a decisive factor in international organization operations, and the minimal focus so far on bilingualism as a requirement for companies in its context - the present study seeks to start filling the gap by looking at a particular linguistic context affecting international company operations: the bilingual context of the province of Quebec, Canada. The research objectives are to conduct an overview of the present literature on both context and language in international business, and thereafter analyze the context of Quebec relative to the existing theories. Based on both the literature and the empirical evidence from the 5 cases used in this study, the aim is to identify the key elements of context, to investigate the channels through which they affect organizations, and finally to explore the resulting phenomena occurring in these organizations.

The research question this study aims to answer is how does a bilingual environment affect international companies operating in that context?

In order to be able to answer the research question in a structured and clear way, it was further divided into three more precise questions:

• What are the components of context?

• Through what channels can context pose limitations and demands to organizations operating therein?

• What kinds of effects can context have on organizations?

1.3 Definitions

Terminology can cause confusion as the same titles are sometimes used quite liberally in management literature. For the purposes of clarity, this section outlines some key terms and the definitions adopted for them in this study.

Context entails the surroundings, forces, and phenomena of the external environment, affecting the focal organization.

Language is a generally agreed-upon, learned symbol system that is used to represent experiences within a geographic or cultural community, and that acts as a carrier of cultural values (Van der Born & Peltokorpi, 2010). A person’s first language is his/her native tongue that he/she feels most comfortable talking. A second language is the next in line when looking at proficiency. Unilingual people speak only one language while a bilingual person is fluent in two languages. Accordingly, bilingualism is a concept or setting where two official languages are employed. Anglophones’ first language is English, and that of Francophones is French.

A multinational company (MNC) is one that owns and controls producing facilities in more than one country (Dunning 1971, 16). A corporate language is an officially designated language to be used in written and spoken communications within the MNC, as to facilitate understanding. Language strategies and policies are formal guidelines on

how to decide which language is used in corporate communication and documentation.

(Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a).

An ethnocentric approach to international HR management involves the emphasis of global integration and spreading best practices and a common corporate language to all parts of the organization. Conversely, polycentric MNCs promote local adaptation according to subsidiary countries. (Van der Born & Peltokorpi, 2010)

1.4 Limitations

As will be explained in more detail in the methodology section of this study, the approach employed in the research is contextualized explanation, put forth primarily by Bhaskar (1998). This involves merging two views often considered opposing, contextualization and theorizing, in order to reach richer description and more workable theories. The aim is to describe how and why events are produced by working backwards in the causal chain. Consequently, the main limitation of this study is its high contextual nature and that the results are generated in a distinct and particular environment. As Devereux and Hoddinott (1993) state, research findings cannot be separated from the context in which data collection and analysis take place.

It has also been cautioned in literature (Cobarrubias, 1983) not to draw too much general theories based on Canada’s case of language policy. Comparing bilingualism in Quebec to e.g. the position of Spanish in America already reveals that the background conditions of the two environments are too unique for findings to be generalized from one context to the other. Bilingualism as a concept varies greatly depending on where it prevails and what the two languages used are. However, since the main approach of the present study was highly contextual and the goal is not to produce universal theories but rather to explore the phenomena occurring in the specific context in question, this was not seen as a major limitation to accomplishing the research objectives.

Regarding the implications of the results, as stated in the research questions the goal is to find the components of context, their channels of influence, and what kinds of effects can be observed at the organizational end. The study does not however aim at exploring effects that go outside the scope of the context in question (the province of Quebec).

Therefore, issues such as knowledge transfer implications between Quebec and organizational units elsewhere are not included in this study.

1.5 Structure of the study

This study is divided into two main sections; the literature review covering the pertinent theories, and the empirical part mirroring them to the findings from the case studies and other data. The first half of the theoretical part deals with the concept of context; first its definition is discussed followed by an overview of research on the topic. Thereafter contextualization is defined and reviewed. Thirdly, ways of dividing context into components and how these components can influence organizations are presented.

Finally, the relevant aspects for the purposes of the present study are combined into a framework to be used in the analysis of the empirical data.

As we will see in the discussion, culture - and encompassed by it, language - are key components of context. In this study, language is a central factor organizations operating in Quebec are forced to consider. Accordingly, the second part of the literature review focuses on language in international business. As with context, we first look at existing research. Thereafter the development of English into a lingua franca of global business is discussed. To meaningfully manage language as a part of context, planning is required, and this activity is examined first on the level of the MNC along with the resulting language strategies and policies. Thereafter focus is shifted to the national level. Finally, we take a look at language skills and training within the MNC. The section ends by answering the two first research questions that can be addressed based on the literature review.

The literature review is followed by a discussion on methodology, namely the qualitative case study as a research method, contextual explanation as a research approach, and the choice of case organizations. Also data collection and verification methods are presented here. The section ends with remarks on reliability and validity. Subsequently the four case organizations and the reasoning behind their selection are presented.

The second half of the study is made up of findings, starting with an analysis of bilingualism in Quebec including its history, the legislation involved - contrasting the national and the provincial levels - and a brief overview of the statistics of bilingualism.

These are contrasted with the theory presented earlier.

The next part mirrors the findings from the case studies to the theoretical framework presented as part of the literature review. The themes are the institutional pressures the context creates on organizational language strategies, the languages actually used in business in Quebec, and the relationship between language skills, training and promotion.

Finally, the effects of the bilingual context on competitiveness are discussed. This section also answers to the research questions based on the empiria.

The study ends with the conclusions section, where main findings are summarized and contrasted to existing research, along with a discussion on their managerial implications.

Finally, suggestions for future research are given.

2. Literature Review

2.1 Context

“Clearly, much research remains to be done before a body of knowledge can be promulgated to the point at which contextual issues become integral to [strategy]. But of context, content, and culture, there is a sense here that the greatest source of inspiration may be context.” (McKiernan 2006a, 5)

Michailova (2011) points out that the nature of the processes and phenomena studied in International Business would let us assume that the discipline treated context as an important explanatory variable. She argues that this is however rarely the case, and that researchers often fail to account for differences in contexts and “treat contextual factors as exogenous variables when they are, in fact, central to the phenomena we research.”

(Ibid, 130) According to Tsui (2004), context can be of great help in clarifying the limitations of existing theories and explaining local phenomena. It can thus assist in deriving new knowledge since it drives the way phenomena are perceived by researchers at a conceptual level (Cai, 2007).

2.1.1 What is context?

Roberts et al. (1978) were among the first to call for more focus on explaining phenomena in a particular, specific context in organizational theory. Thereafter, Das (1983, 393) claimed that “any serious discussion of a phenomenon can happen only if its contexts (of occurrence) are carefully described and studied”. Contextual factors in research started attracting increasing attention towards the end of the 1980’s, with Lincoln & Guba (1985) and Pettigrew (1985) arguing for research as a social process, not a rational application of techniques. In 1991, Cappelli & Sherer defined context as the

“surroundings associated with phenomena which help to illuminate that phenomena, typically factors associated with units of analysis above those expressly under investigation” (1991, 56). Subsequent definitions in Mowday and Sutton (1993, 198) and

George & Jones (1997, 156) outlined context as “stimuli and phenomena that surround and thus exist in the environment external to the individual, most often at a different level of analysis” and “the environmental forces or organizational characteristics at a higher level of analysis that affect a focal behavior in question”, respectively. A more recent view by Johns is that context entails the “situational opportunities and constraints that affect the occurrence and meaning of organizational behavior as well as functional relationships between variables” (2006, 386). Finally, Marschan-Piekkari et al. (2004, 245) argue that context can be seen as both the environment of the phenomenon under study and the research setting constructed.

As McKiernan (2006b) states, the treatment of contextual factors has wandered between prominence and obscurity in literature. Their definition depends largely on what phenomena one seeks to study and explain. Should this be the behavior of individuals in organizations, context can be seen to include workplace conditions, broader social or normative environments (i.a. dimensions of organizational or national culture, or unit or organizational climate). On the other hand, when studying the behavior of organizations themselves, context may encompass industry-, sector-, or economy-wide characteristics, and other normative and institutional structures, as is the case in this study (Bamberger, 2008).

For the purposes of the present study, the definitions in Cappelli & Sherer, George &

Jones and Mowday & Sutton are most suitable. Combining them we can say that context entails the surroundings, forces, and phenomena of the external environment, affecting the focal organization. We now turn to the relationship between context and the research process.

2.1.2 Contextualization

Several research handbooks stress the intertwined relationship of qualitative research and context, and how it essentially distinguishes qualitative from quantitative research (e.g.

context presents two types of challenges to research. From the theoretical perspective, contextual processes and phenomena should be incorporated into academic explanations.

On the other hand, the researcher should acknowledge - and adapt to - the impacts context has on the research process itself. The past three decades have brought a considerable volume of studies on national and cultural contexts and on how to take their effects into consideration during the research process (see e.g. Devereux & Hoddinott, 1993; Rousseau & Fried, 2001; Johns, 2001). More recently, the effects of the organizational context on research in international business - more precisely, the research interview - were discussed by Marschan-Piekkari et al. (2004).

The general description of contextualization is that it involves linking observations to a set of relevant facts in order to generalize findings and make their interpretation more robust (Rousseau & Fried 2001, 1-2). Contextualization has increased in the past years and several management and organizational behavior journals have started to encourage authors to provide more sophisticated accounts of context (Johns, 2006). As Bamberger (2008) suggests, however, this is typically a post hoc exercise aimed at informing the reader about the factors influencing study results. This approach to context differs from that of the present study. As described above, context has historically been seen as a background factor and an account of the research setting. Studies usually focus on a phenomenon X in the context Y; the context itself is rarely the focal point of research.

The present study turns the traditional approach around and puts the bilingual context of Quebec - and namely its effects on international company operations - in the spotlight.

Bamberger (2008) critiques contextualization for its often-superficial nature and suggests we should instead be working on context theorizing: building situational and/or temporal conditions directly into theory. International business by definition deals with different locations and populations, and thus different contexts (Tsui, 2004). Michailova (2011, 132) states, along the lines of Bamberger (2008), that “there is a distinction between dealing with different contexts ‘per definition’ and addressing explicitly those contexts in theorizing, in applying methods, in conducting analyses and in articulating findings”.

She laments that the definition of IB and the assumption that it inherently transcends

national contexts not always means researchers in the field succeed in integrating contextual effects into their work. The present study seeks to do a better job in this area, and to avoid what Martinez & Toyne (2000) describe as merely transferring context- bound theories across contexts. As Welch et al. (2011, in Michailova 2011) offer, the most interesting IB studies are those that intertwine context with research evidence to explain the phenomena under investigation, and this combination is what the present study seeks to accomplish.

2.1.3 Components of context and their channels of influence

Depending on the definition of context, different classifications for it exist in research.

According to a similar logic as e.g. Marschan-Piekkari et al. (1999b) use for classifying the different languages used in a multinational, also context has been divided into the rationalities of local organizational context, the subsidiary’s host country context, and the national context of the parent company’s home country (Geppert & Matten, 2003). In the present study this classification is not purposeful, as the goal is not to go beyond the host or home context of the subsidiaries or parent companies operating in Quebec. In the framework of MNCs, also Kostova (1999) distinguishes between three types of context:

social, organizational, and relational. This author uses the term social context synonymously with Scott’s (2001, 49) institutions: the “multifaceted, durable social structures, [that are] made up of symbolic elements, social activities, and material resources”. The elements of social context are further discussed in the next paragraph.

Organizational context refers to the compatibility of organizational cultures and practices, and relational context to commitment, identity, trust, and power/dependence relationships. As Kostova studied knowledge transfer between home country and recipient, the mentioned definitions refer to this dependency. As this relationship is outside the scope of the present study, Kostova’s classification is not ideal to use here.

The element of social context, however, is noteworthy for this study, and we now look at Scott’s approach to it as institutions.

Scott (2001, 51–57) recognizes three pillars of institutions: the regulatory, normative, and cultural-cognitive. Each component involves specific channels through which it can affect organizations; 1. The regulatory context reflects the existing laws and rules of the environment, promoting certain behaviors and restricting others, through reward and punishment. 2. The normative context includes values - conceptions and standards of the preferred and desired - and norms - the way things should be done, and thus defines the appropriate means to pursue defined goals and objectives. 3. The cultural-cognitive context involves the shared conceptions making up social reality and affecting the way people notice, categorize, and interpret stimuli from the environment.

Also Redding (2005) explores institutions in his discussion on societal systems and capitalism, and divides them into the formal and informal kind. Formal institutions include more or less visible and tangible structures, such as legal systems. Their channels of influence are thus more prominent and visible in the operating environment. Informal institutions exist at a deeper level of culture, shaping the formal kind. It is also important to note that outside influences shape all societies, and do their part in forging the development of institutions.

Institutions can also be seen as an interest group. Interest groups can be defined as organized collective actors (e.g. unions, professions, or owners) representing particular societal positions and competing to obtain a share of resources or other benefits. Their structure, significance, and impact vary between societies. (Porter & Wayland, 1995) As per this definition, the impact institutions can have on organizations differs from one business environment to another, but their key characteristic is that they have certain interests they seek to advance. This happens through the channels discussed above.

Redding (2005) proceeds to propose a highly contextualized theory of business systems.

In it culture underlies institutions, which in turn underlie business systems. He builds on the views of Whitley (2003) to suggest that firm behavior is deeply embedded in their socio-political-economic-historic contexts. In the present study, particularly the political and historic perspectives are pertinent. However, the goal is not to study the cause-and-

effect relationships between the different components of context, but rather the effect they together have on the organizations. Figure 1 illustrates the accordingly modified framework of Redding (2005), where culture, business systems, and institutions are all embedded in the political-historic context they operate in, and thus have their effects on firms operating in that same context. In this study, especially the political-historic context and institutions are focal points of interest. In the figure, language is incorporated by culture, but as we will see later on it can be analyzed also from the political-historic and institutional perspectives.

Figure 1. Elements of context and their effects on organizations (modified and combined from Redding 2005, 133 and Lewin & Volberda 1999, 528)

History is thus an important component of context. Redding (2005) argues that history molds the background context, and without it accounts of current economic systems are incomplete. He emphasizes the role of history in providing trajectory of development, and distinguishes between two channels of influence: specific historical events, and conditions that during a specific period shaped an environment. Historical factors are often excluded in international business studies, though as Redding (2005, 131) points out, their “explanatory contribution is commonly too significant to remain untreated”.

This angle is particularly relevant in the present study, as will be seen in the empirical part.

Sorge & Brassig (2003) studied small German enterprises and argued for a co- evolutionary approach when looking at organizational strategy and environmental determinism. That is, incorporating historical context, change within institutions, industries, and firms, as well as surrounding economic, social, and political macro- variables, into the research. In the background is the theory of organizations resulting from a co-evolutionary interaction between the construction of environmental niches, organizational form, and context, guided by strategy (Lewin & Volberda, 1999).

Also an element in Michael Porter’s (1990) theory of competitive advantage is pertinent to the concept of context. As at the core of this thinking is that an organization’s comparative advantage resides where it is based, location and environment become central factors benefiting or impairing operations, contrasted with competitors elsewhere (Porter & Wayland, 1995). A set of factors Porter (1990, 647–649) distinguishes as potentially undermining competitive advantage are governmental regulations. These might be e.g. standards on production, safety, environmental impact, or the operating practices of a firm. Porter notes that regulations can act both in favor of and as a hindrance to competitive advantage. They can serve as entry barriers when they render the operating environment unattractive, and also make it difficult for local firms to develop advantage. Positive effects can result when regulations anticipate standards and thus encourage firms to develop their practices ahead of competitors elsewhere. But when regulations are formed with a short-term focus or lag behind those of other nations, they can be detrimental to competitive advantage. Additionally, only efficient and agile standards that are applied consistently can contribute to competitiveness, whereas slow, uncertainly applied, and outdated regulations undermine innovation and competitive advantage.

In this section we have looked at context from different perspectives. To provide background, the historical treatment of context in research was examined and found to be quite rare to date. Especially more specific, micro-level contexts (such as a province within a country) have been studied scarcely, with the exception of intra-firm contexts.

Research on broader, national contexts is more common. Thereafter, different definitions

of context were presented, out of which a suitable one was combined to suit the purposes of this study: context includes the external surroundings, forces, and phenomena affecting the organizations operating therein. Next the role of context in the research process was discussed, as well as the challenges it creates to researchers. One of them is contextualization, which entails the linking of observations to relevant facts in order to generalize findings. As a research activity this was found to remain rare, though it has become more common in studies in recent years. Context theorizing was presented as more evolved approach; incorporating situational and temporal factors directly into theory.

Subsequently, different ways for classifying context were introduced, and out of these the notion of social context was distinguished as most pertinent for the present study. Instead of social context, institutions were found to serve as a better framework, as it incorporates the social aspect (shared conceptions of reality), and divides into two additional components; the regulatory (laws and regulations), normative (values and norms) kind.

Institutions can also be classified into informal (deeper levels of culture) or formal (e.g.

laws), with the previous shaping the latter. Moreover, institutions can be seen as an interest group, competing for resources and attempting to forward their own goals and to impact organizations. Finally, history was discussed as an important, yet often ignored component in understanding context, as particular events or periods in time can significantly forge the setting in which we live today. Combining all these components, a conceptualization of context was developed, in which culture, business systems, and institutions are embedded in and affected by the political-historic context surrounding them. Organizations operating in the same context are then effected by these elements.

Finally, a point was made about regulations as a factor of competitive advantage. They were noted to have potential to boost or impediment competitiveness, depending on whether they are efficient and anticipate international standards (advantage), or are outdated, sluggishly applied, and lag behind other nations (hindrance).

The second chapter of the literature review goes in more detail into language, which is a central component of context in the framework of this study.

2.2 Language in international business

Even though International Business as a discipline by definition entails the examination of different geographical, cultural, and thus linguistic contexts and areas, language long remained as a relatively unexplored topic in management literature. It has often been bundled together with the wider definition of culture, or psychic distance, and therefore received little attention as having an independent and influential role in international business (Welch et al., 2001). Indeed, several articles over the past two decades have pointed out the lack of research on the subject, calling it “the forgotten factor”

(Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1997) or “the most neglected field in management” (Reeves &

Wright, 1996). Luo & Shenkar (2006) also recognize the lack of studies focusing on the strategic role of language in IB, and argue that language does have an impact on strategy since subunit language design influences local responsiveness, and parent language design in turn affects global integration.

Especially coming into the 21st century, language issues have gained more prominence in literature, and scholars have started to stress their importance and significance that warrant a more focused approach (e.g. Welch et al., 2005). Peltokorpi (2007) has argued that separating language from cultural values has allowed researchers to explore and present its strong influence in a range of issues in MNCs. These include i.a. intercultural communication (Andersen & Rasmussen, 2004), social interaction (Tange & Lauring, 2009), coordination, control, and structures (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a), and knowledge transfer (Mäkelä et al., 2007). Consequently, an example of a strategic area where language effects have been examined is the internationalization process; it has been found that firms have a tendency to stay within the language group where their initial competence resides, as to minimize the demands and risks of having to operate in a new language (Welch et al., 2001). Also the HQ-subsidiary relationship and the implications of language to its functioning have been studied (e.g. Harzing et al., in press;

Harzing & Feely, 2008; Barner-Rasmussen & Aarnio, in press). A need for a common language in international business has arisen from these challenges. As the following discussion shows, this position is today widely held by English.

2.2.1 English as a lingua franca of business

In 1988, John Davidson - the director of the Confederation of British Industry at the time - stated: “English is no longer the international language of business. Today’s international language of business is the native language of the customer.” (Duncan &

Johnstone, 1989 in Visser, 1995). Visser (1995) later criticized this view as an unattainable ideal, arguing that few companies can afford to invest in being able to speak the languages of all potential customers. Instead, they set priorities and realistic targets regarding language competencies in order to achieve export goals.

A phenomenon occurring in research on the adoption of English as a corporate language is the “English divide” discussed by Rogers (1998); the perspective on the matter can be either that of English as a cultureless and neutral language, as an imposed obligation resented by those having to learn it, or as deemed fitting by the international business community. She suggests that due to this divide, two types of research can be distinguished: the multilingual research arising from countries where English is a foreign or second language, and studies prioritizing English that originate from the English- speaking world. But as Nickerson (2005) laments, the larger part of research on English in international business contexts has been relatively uncritical, taking the use of the language as a given and a neutral means of communication disassociated with any culture. She calls for more research with a collaborative element (involving multilingual settings and non-English researchers) in order to shed light on business discourse as a

“creative, strategic activity” (Ibid, 378). The present thesis looks at the use of English in a specific linguistic context instead of discussing it as an isolated factor. Such work in the area is still rare apart from some exceptions (see e.g. Fredriksson et al., 2006).

The emergence of English as a lingua franca of global business is explained by House (2002, in Frendriksson et al., 2006) by several factors: 1. The historical widespread rule of the British Empire, 2. The global political and economic influence of the USA, 3. The development of modern information and communication technologies, and 4. The increase in international merger and acquisition activity. On the other hand, as companies

internationalize and expand, they inevitably start consisting of a more and more diverse workforce with regard to nationality, culture, and language. This is a key aspect in a MNCs ability to be locally responsive and serve each foreign market according to its specific needs. (Dhir & Gòkè-Pariolá, 2002) To deal with the communication issues emerging from this linguistic diversity, several MNCs have opted for a common corporate language. Zaidman (2001) stresses that a common language for internal communications becomes even more critical with increased resource sharing within a globally diversified MNC. This can also be referred to as ‘language standardization’, which has been said to bring the following advantages (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a):

1. If facilitates inter-unit reporting, minimizes miscommunication, and allows everyone equal access to company documents,

2. It enhances informal communication and information flows between subsidiaries, 3. It fosters a sense of belongingness and togetherness.

Because of the dominance of English as a universal business language, it is often the choice of companies going for one official corporate language (Marschan-Piekkari et al.

1999b, Charles & Marschan-Piekkari 2002). Yet, as Fredriksson et al. (2006) present, the mere introduction of English as the language of internal communications does not mean it will actually be adopted, used, or shared throughout the organization. Indeed, MNCs are multilingual by definition, and consequently a common corporate language will not create a monolingual firm, but language diversity will persist within the company (Andersen & Rasmussen, 2004). As the adoption of a common corporate language requires a substantial amount of people in a MNC to be bilingual, it creates challenges for international human resource management practices (Van der Born & Peltokorpi, 2010).

An important divide exist between the managerial and lower levels of the organization;

the perception of English as a universal language of business tends to be particularly strong among top management, who have good command of it after e.g. English MBA programs (Tietze, 2004). Also Feely & Harzing (2003) found that employees at lower hierarchical levels are more likely to only speak the local language, and that it takes some time before the common corporate language penetrates the entire organization. These authors identify language penetration as a component of language barriers caused by

cross-cultural communication within MNCs. Previously, it was often enough for a small, exclusive group of language specialists to channels cross-lingual communications.

Today, however, due to global coordination, higher language penetration is required and language competence needs are often a reality on all corporate levels, including supporting functions.

Consequently, in the process of implementing a common corporate language, some members of the organization often have a language advantage, while others might be excluded from critical information exchanges (Charles, 2007). Due to these factors, as Janssens et al. (2004, 415) argue, “international companies are multilingual organizations in which language diversity needs to be organized”. MNCs thus have the need to deal with their language diversity in a meaningful way, i.e. develop some kind of language strategies, or at least policies. These will be discussed next, and thereafter language planning on the national level is reviewed.

2.2.2 Language policies and strategies of MNCs

As Dhir & Gòkè-Pariolá (2002) point out, the changes occurring in the global business world would suggest it to be imperative for MNCs to take a serious look at the development of language policies. Nevertheless, research on the topic is still rather inadequate, and so are actual language strategies in MNCs. Marschan-Piekkari et al.

(1999b) recognize that a relatively large amount of studies exist on the internationalization process, but the language issues resulting from global expansion - and how some companies introduce a common language as a solution - are still quite unknown territory.

Why is it then important to generate language policies? As Dhir & Savage (2002) develop: language is the means by which the culture of an organization is communicated to its members, and by which value creation is facilitated through the exchange of ideas.

Language can therefore be seen as a repository of an organization’s knowledge; “Like

(Ibid, 2). The authors offer a process for the evaluation of the economic value of languages for an organization for the purposes of choosing the most suitable one to use.

Luo & Shenkar (2006) suggest that good management of the language issue in a MNC has the potential to improve intra-network communication, inter-unit learning, parent- subsidiary coordination and integration, and intra-unit value creation.

Language policies are formal guidelines on which languages to use in corporate communication and documentation (Marschan-Piekkari et al., 1999a). Van der Born and Peltokorpi (2010, 100) propose a classification of language policies based upon the global integration vs. local adaptation trade-off facing MNCs. According to these authors, language policies should be aligned with HRM practices according to ethnocentricity, polycentricity, or egocentricity, depending on the strategic orientation of the organization. Firstly, ethnocentric MNCs emphasize global integration and seek to spread best practices and a common corporate language to all parts of the organization. These kinds of language policies are formulated for enhanced control, communication, and coordination, and usually prevail in countries concerned with value homogeneity, and not so much foreign language competence. Conversely, a MNC with a polycentric orientation carries out local adaptation, differentiating practices according to local subsidiary environment and with limited control from headquarters. These organizations require corporate language proficiency on the managerial level, but subsidiaries often use the local language. Finally, a geocentric strategic orientation from the IHRM perspective involves recruiting managers from a global candidate pool. As Van der Born &

Peltokorpi (2010) point out, this approach amplifies the need and importance of a common corporate language and its proficiency amongst managers. Moreover, it has been shown in studies that even when language policies would let us assume that competence is at a certain level in the organization, this is not always the case, especially in countries where the general second language proficiency is low (see e.g. Marschan- Piekkari et al. 1999b, Peltokorpi 2007). This may result from a country’s national language policy, which organizations may need to consider as a powerful factor in their external context.

2.2.3 National language planning

As recognized by i.a. Dhir & Gòkè-Paríolá (2002), language planning in MNCs is a relatively new activity. On the national level, however, language planning and policy have a longer history. In sociopolitics, language planning is defined as “a government authorized, long-term, sustained, and conscious effort to alter a language’s function in a society for the purpose of solving communication problems” and it involves “complex decision making, the assignment of different functions to different languages or varieties of a language in a community, and the commitment of valuable resources” (Weinstein 1980, in Dhir & Gòkè-Paríolá, 2002).

Wardhaugh (2006, 357) distinguishes two types of language planning: status and corpus planning. Status planning involves the position of the target language or its varieties in relation to others. Policies resulting from this kind of planning may better or diminish a language’s status compared with others. A government can for instance declare that two languages instead of one will be officially recognized in all functions. In this case the new language gains status; instead of having no official position it is now used alongside the other official language in public communications. Most often, however, status change happens gradually, and at the expense of another language’s position. In an extreme case this can lead to linguistic discrimination that raises contest and leaves strong residual feelings, as is the case e.g. in Canada. Corpus planning in turn entails the internal constitution of the target language with the goal of changing it. The result is usually a policy that attempts to standardize a language as to have it serve all possible functions.

This may include developing new vocabulary and dictionaries. These two types of planning are not mutually exclusive and usually co-occur.

Different philosophies may underline the linguistic decision-making and policy planning in societies. Cobarrubias (1983) identifies four such ideologies:

1. Linguistic assimilation requires everyone in the society speak the dominant language. France is a good example of a country with such a policy.

2. Linguistic pluralism involves the coexistence of multiple language groups, and it can be found e.g. in Switzerland where four different languages are employed.

Linguistic pluralism can be regionally or individually based, or both, and this is reflected in the overall language policy of the country employing it. Canada and Belgium are other examples.

3. Vernacularization involves the restoration or elaboration of an indigenous language in order to adopt it as an official language.

4. Internationalization is the common alternative of today’s corporate world, and can be said to be behind the ideal of a common corporate language as a facilitator of internal communications across country borders. The languages that have been most internationalized are French and English, with English much ahead in volume. La Francophonie as an organization has been set up to further French globally, and is a manifestation of the internationalization philosophy (Wardhaugh 2006, 358).

Language issues can be closely linked to identity and power because of the strong connections between certain languages and nationalism (Fredriksson et al., 2006). This is very much the case with French, which can be seen in the considerable protectionism of the language in France and other Francophone countries of the world (e.g. the regulation of the amount of English in media).

These two levels of language planning create specific linguistic demands for international HR management activities, especially the need to manage language skills of employees.

Therefore, even though language training and the effects of language skills on promotion are not among the focus points of this study, they need to be discussed briefly to provide background to the empirical findings.

2.2.4 Language skills, training and promotion

In this section we review the implications of language skills on training needs as well as promotion and advancement within the organization.

Language training

The importance of knowing the corporate language may differ according to what kind of strategic approach the organization has taken towards the language issue. In an organization employing a polycentric approach where practices are differentiated according to local units, the local language might be enough especially on lower hierarchy levels. However, with an ethnocentric strategy language competence becomes a lot more critical. (Van der Born & Peltokorpi, 2010) As most MNCs with this orientation recognize the need for corporate language proficiency, they offer language courses for employees. According to Van der Born and Peltokorpi (2010), especially when using the corporate language is considered to lower inter-group boundaries, language training should become available. They however note that language training, whether it is provided at the headquarters or at subsidiary level, may not be equally accessible to all employees. Also, language training is an expensive activity. While larger companies are able to maintain their own language-training facilities, smaller organizations often see acquiring such training as a financial burden (Dhir & Savage, 2002).

Language and promotion

As Fredriksson et al. (2006) have found, the higher up one goes in an organization, the more important language skills become. In the study of these authors, language competence was discovered to be a requirement for reaching the managerial level at Siemens. However, it was also found that English, even though the official corporate language, was not required nor mastered in all parts of the organization.

It has been found by several authors (e.g. Fredriksson et al. 2006, Marschan-Piekkari et al. 1999a) that proficiency in the corporate language is often a pre-condition for promotion to managerial positions because of increased interaction between expatriates, headquarters, and other foreign subsidiaries. As Marschan-Piekkari et al. (1999b) note, this can turn language into a determinant of professional competence and cause certain individuals or groups to have gate-keeping positions and to channel information, increasing their power within the organization. This type of individuals are often referred

to in literature as “language node”, that is, people who because of their superior language capability become crucial in communications, translating and transmitting information between parts of the organization (e.g. Welch et al. 2001). The final topic regarding language is the reality of language use within a MNC, which is shown to not necessarily coincide with official strategies.

2.2.5 Languages used in MNCs

As stated above, the appointment of a common corporate language as a solution for the language issue in a MNC does not render an organization unilingual, nor eliminate linguistic diversity. Even with language training available it is not guaranteed, or even common, that all employees will be able to function in the corporate language, especially in organizations employing a pluralistic or polycentric approach to strategy where local adaptation is encouraged. It has been found that even though the role the corporate language is assigned in official language policies would suggest widespread proficiency in the MNC, the competence may not in reality exist, especially in countries with a low general second language level (i.a. Marschan-Piekkari 1999b, Peltokorpi 2007).

Nickerson (2005) found that in reality language use does not often follow the rule of purely one language a day, a meeting, or even a sentence. In her study of a multilingual company she observed a co-existence of multiple languages, and occasionally a hybrid form involving two languages, randomly switching between them for a sentence or just a word. Needless to say, this kind of speak would be impossible to follow for someone mastering only the other language.

This second section of the theoretical part started with an overview of language in managerial and IB literature, where its novelty as a standalone topic was demonstrated.

The strategic implications of language for MNCs have however attracted increasing attention coming into the 2000’s. Be that as it may, Bilingualism was noted to remain a scarcely studied topic in the field of business. Next, the concept of English as a lingua

franca of business was discussed, including the factors having affected its development into a universal language of business, the different attitudes towards the issue between disciplines, and their effects on research. Here we saw that the tone of research usually differs considerably based on its origin, and studies coming from non-Anglophone countries usually have a broader perspective on the matter. Thereafter linguistic diversity in MNCs was reviewed as well as the resulting need to manage the language issue in a purposeful way, and the designation of a common corporate language was shown to be a popular solution. In line with the widespread use of English as a business language, this was noted to often be the choice of multinationals for corporate language. However, it was also pointed out that this does not create a unilingual firm, and that corporate language competence may vary considerably within the organization.

These developments boil down to the need for language strategies and policies. These were first examined on level of the MNC, where language policies were defined as formal guidelines on which language to use in corporate communication and documentation. Three strategic orientations were found in international HR practices when it comes to dealing with the language issue: ethnocentricity (global integration and spreading the HQ home country language in all parts of the organization), polycentricity (local adaptation and using the subsidiaries’ home country language in sub-units), and egocentricity (applying a global philosophy to recruitment and thus requiring proficiency in the corporate language). From this division focus was shifted to national level where language policies result from both status planning (changing a language’s position in relation to others), and corpus planning (developing the language to suit all purposes).

Additionally, four language planning ideologies were presented